This is an excerpt from my book proposal “Footprints of the Enlightened Ones”. Sending warm greetings. All is well here. I’m grateful for lovely summer weather in the forests of Paro.

There are secrets in the mountains of Bhutan. And deep memories in flesh and blood. Not sure where to begin my story. But before I can tell you about the Tshechu dancers, we have to go back to the 8th century to meet the famous Guru Rinpoche. Even his name conjures a link between Indian “Guru” and Tibetan “Rinpoche” traditions. Yes, he was both. Padmasambhava traveled far and wide, meditating in countless caves throughout Tibet, Nepal, and Bhutan.

This man was a game-changer, a brilliant renegade wizard who came to Tibet and oversaw the translation of thousands of sacred texts from Sanskrit to Tibetan. He performed miracles and eloped with not one but two princesses. He cleared evil and infused the landscapes of Tibet and Bhutan with powerful blessings that still exist today. Maybe that’s why every dzong in Bhutan has a huge statue of him with burning eyes, long hair, a diamond-vajra scepter of compassionate love in his right hand and a skull-bowl of wisdom in his left. In short, don’t mess with this guy.

Padmasambhava is said to have been born about 700 years after Christ in NW India. He traveled and studied with many great Indian masters and somehow learned wizardry to purify negative obstacles, making the way for new Tibetan Buddhism. Nowadays most of Bhutan’s Buddhists follow his Drukpa Red Hat sect of the Kargyupa, or “Secret Oral” lineage of Tibetan Buddhism. Yep.

Padmasambhava was a magician that Bhutan sorely needed. He came almost 1,000 years after Siddhartha, the popular Gautama Buddha, who lived in 500 BCE. But even before that, a long lineage of Buddhas, or “awakened ones”, lived and taught in the Himalayas. We could look even further back to the roots of Bön Buddhism in Tibet, where the “first known Buddha”, Tonpa Shenrab Miwoche, is said to have lived 18,000 years ago. But it seems the floods may have washed everything clean, and alas, we will never know. Human memory fades, as do all things impermanent. Perhaps the real memories lie in the rocks, bones, and the blood.

Buddhists never considered their practice to be a “religion”, but rather a personal journey of purification into the Truth, a study of Nature and universal Time. I suspect that when the term ‘Buddhism’ was coined by Western scholars in the 1830’s, it was after seeing huge statues, and assuming that the Buddha was worshipped as a God, instead of being just man who found a path to be free.

Another major player in reviving deep cultural memories is the charismatic Fourth King of Bhutan, Jigme Singye Wangchuck, who has played a crucial visionary role in expanding the Tshechu festivals. He believes that the foundation of unity and sovereignty is a strong cultural identity and shared link with cultural roots. He took the throne in 1974 upon his father’s death when he was only 19 years old.

His great grandfather was Bhutan’s first king, Ugyen Wangchuck, a magnetic leader who came to power during a turbulent period of bitter internal feuding and British wars. But Ugyen Wangchuck didn’t fall for the imperialistic spell. He was smart. A few strategic battles ended in a peaceful arms-length treaty, and in 1907 the British walked out. They supported his throne and left Bhutan to be one of the only independent nations in Asia, and not beholden to the crown.

Building Bhutan’s national awareness of their Buddhist cultural roots has been one of the many contributions of the Fourth King. But there’s more. He established two democratic houses of Parliament in a Constitutional Monarchy. He instituted national health services, safe drinking water, better nutrition, increasing life span, and founded the Royal Institute of Health Sciences. He introduced an unconventional tourism policy of “high-value, low-volume”, unique in the world, to invite and guide visitors through Bhutan’s cultural sites, protecting the economy and environment. He built a network of electricity to connect homes, constructed roads in impossible mountain terrain, and began a Bhutan-owned air service. He signed an ambitious hydropower project to sell waterpower to India, stabilizing Bhutan’s financial independence. Then after ruling 34 years, in 2006 he abdicated to his eldest son. I think probably he gets more work done behind the scenes.

Gross National Happiness Surprises the World

Perhaps the Fourth King’s most significant contribution was to introduce the unique philosophy of GNH, Gross National Happiness. A philosophy designed to balance spiritual and economic values, the term became instantly popular in 1972 when the Fourth King declared at the United Nations: “Gross National Happiness is more important than Gross Domestic Product.” He then developed a method to measure happiness by a questionnaire to a sampling of the population every year, with a statistical score that compares one year to the next.

Happiness has been a core goal of Bhutan for four centuries. In fact, the concept has its roots in the Buddhist Legal Code of 1629 (Yes, 150 years before the 1776 US Declaration of Independence set forth unalienable rights to “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness”). In 1629 Bhutan’s founding father declared:

“If the government cannot create happiness for its people, then there is no purpose for government to exist.” Zhabdrung Rinpoche, founding father of Bhutan

GNH, the Quintessential Buddhist Economic Policy, Consists of Four Pillars:

- Sustainable and equitable socio-economic development.

- Conservation of natural environment.

- Preservation and promotion of culture including National identity, Religion, Language, Literature, Dress, Art, Architecture, and Etiquette.

- Good Governance.

Building a National Identity of Respect

How can one inspire strength and unity in an ancient, pay-it-forward Buddhist culture? It takes good leadership to feed the deepest roots of well-being in people. A visionary wise ruler, the king has infused Bhutan’s identity with self-respect. Fostering ancient legendary dances strengthens non-verbal connections to the subconscious to build inner self-awareness, a pride of belonging that protects people. Otherwise lacking this level of visionary leadership, people are too vulnerable and easily succumb to the vast international invasion of technology, junk food, money, English, and Hollywood fantasy. I wonder: What does Bhutan understand that we don’t? What can the rest of the world learn from Bhutan?

Enlightened Tourism

Tourism too much, too fast can rob a country of its traditions and dignity. On the other hand, gentle tourism can infuse respect while helping economically. The Fourth King’s “high-value, low-volume” tourist policy provides a middle-ground solution. He structured a tourism industry that fosters high-integrity tour operators that bring visitors to Bhutan for an all-inclusive minimum price of $250 per day in high season, a fee that’s comparable to any standard vacation in Maui or Milan.

But even the best tourism policy can’t always build cultural understanding. Why is that? The biggest roadblock is that we Westerners observe but cannot see. We hold fast to our cell phones and zoom lenses, appreciating the colorful costumes and endearing traditions from a safe distance, without having to risk totally jumping in. Full immersion might mean giving up our personal space, enduring the same discomforts, accepting what comes, looking at a history of white domination, reaching into underlying assumptions and values of another culture. Nope, we think we can come for a brief visit, pay our money and walk away unscathed.

But in my case, I was enthralled. I wanted more of the mysterious traditions, colors, and legends. This immersion in powerful invisible non-verbal threads from the past shook me to the core and nourished a deep inner longing.

Origin of the Tshechu Dance Festivals (pronounced TSEH-choo)

Legend has it that when the great saint Padmasambhava performed feats of magic and wizardry to protect Bhutan and its people from evil, his rites, mantras and dances involved taking on other identities. Thus he was able to perform miracles, in order to subjugate and transform opponents of Buddhism into loyal followers.

Padmasambhava is credited with having organized the very first Tshechu in the 8th century, consisting of a series of eight ritual dances. Over time, these dances have expanded and now come to illustrate different legends in the victory of good over evil, a powerful expression of Bhutan’s unique cultural and religious identity.

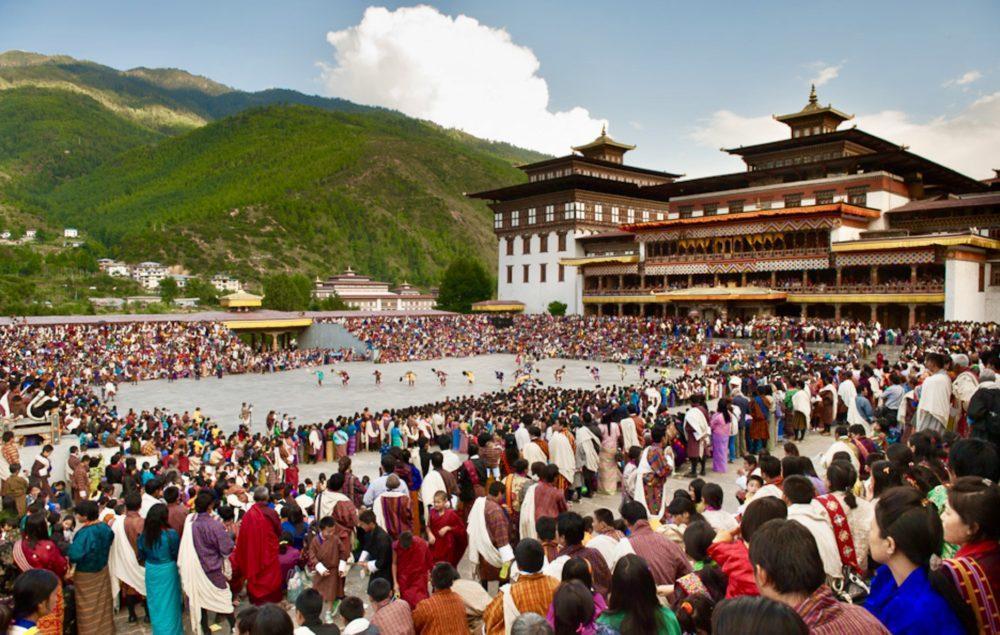

Every monastery in Bhutan holds one Tshechu each year, where hundreds of Lamas and Monks enact ancient stories in animated sacred dances and songs. Tshechu means “10th day”, so each province holds their festival on the 10th day of their chosen month in honor of the birth of Padmasambhava. The Tshechu has become so important in each city, that everyone dresses up in their finest Kira or Gho to see, to be seen, to sing, dance, and receive blessings. It is believed that every Bhutanese person must attend at least one Tshechu every year to cleanse the spirit and live in harmony with the unseen world.

Buddhism teaches that events don’t just “happen” out of nowhere. Although we may imagine ourselves to be independent, all events have roots in the past. This is the magic of life, where heroes and perpetrators are all connected, weaving like threads into patterns that determine our fate. Thus the Tshechu legends are real shared history. By strengthening the roots to memories, tribe, and family, the Tshechu is a gift to remember ancient roots, national identity and self-respect.

People’s deep faith and devotion make the Tshechu festivals special occasions. Yes, the carnival excitement is palpable, but this is quite different from a ball game in the US where a crowd goes wild about a ball going into a goal. A Tshechu is an enactment of ancient shared memories that’s unique in the world.

Tshechus are the fusion of religious festival and social bonding shared by people of many remote villages. Bhutanese believe coming to a Tshechu blessing will purify them and help them live in harmony, health, and wellbeing.

Long before the Tshechu date and behind the scenes, Monks and Lamas are preparing in deep meditation, chanting, and dance practice. The Tshechu is a rich form of oral history, a tradition where the Bhutanese pass on values, mythology, and spiritual beliefs through the dance dramas.

Festivals are also a big family and social occasions. My new sisters and I all put on our best Kira’s with jewelry of coral, turquoise, and Dzi beads. We packed lunch in a traditional bamboo basket and stayed at the monastery all day. Seating is first-come, first-serve. When we arrived at 10 am, parking was crowded, the monastery courtyard was packed with thousands of people, and more continued to arrive all day. Those who got the best seats must have been in line at the crack of dawn. That’s what I’ll do next year.

The most popular Tshechus in Bhutan are:

- Paro Tshechu –March

- Thimphu Tshechu – October

- Jambay Lhakhang Tshechu – November

- Punakha Drubchen and Tshechu- February

- Ura Yakchoe – April

Many of the Tshechu dances enact events from the life of Padmasambhava, to invoke protection, to illustrate the subjugation of demons and obstacles, and celebrate the victory of good over evil. Like a live theater, dancers act out stories such as the Dance of the Four Stags, The Three Kings, the Dances of the Lord of Death, and more. Modern jesters called “Atsaras” wander around creating mischief, performing short skits to disseminate health and social awareness messages. A Tshechu is a happy and necessary break from farm work, a time to celebrate, receive blessings and pray for happiness.

“Monks and Lamas believe that through their dances enacting ancient legends, they send blessings throughout the world to purify karmic debts and empower

all beings to reach their highest destiny.”

My personal favorite dance is the Tungam Chham, Dance of the Terrifying Deities. This sacred scene acts out a ritual slaying of evil demi-gods, enemies of the Buddhist path. The so-called “Terrifying Deities” wear the most lavish costumes – silk brocade skirts, tall boots, and frightening masks showing off long fangs and skulls. The scene portrays a ritual sacrifice where dancers represent evil “Asuras”, the demi-gods, who are encircled and captured in a box. The chief dancer stabs and kills them with a sacred dagger called a Phurba, thus saving the world from their evil deeds and at the same time delivering them into salvation.

In the Dance of the Terrifying Deities, the hideous masked face of Dorji Dragpo “Fierce Thunderbolt”, is said to be the image that Guru Rinpoche assumed to subdue enemies of the path. His selfless victory eradicated the evil demons, leading to happiness and goodness in the world.

I was blown away by the display of finery worn by everyone at the Thimphu Tshechu. The women especially were decked out in brightly colored handwoven fabrics and jewelry that would cost thousands of dollars in a New York showroom.

The Kira for women consists of a wrapped hand-woven skirt tied with a Kera or belt. A colorful silk blouse called Tego is worn with a silk jacket called a Wongu, with sleeves rolled together into a cuff. Women often wear large amounts of jewelry with the Kira, set. For formal occasions like Tshechu, women wear a narrow handwoven fringed sash over the left shoulder called a Rachu. The whole ensemble is stunning and Bhutanese women look elegant in their national dress.

The man’s Gho is a knee length cloak that’s tied at the waist with a cloth belt called a Kera. A Gho has white cuffs that can be folded or pinned in place. Ghos come in a wide variety of handwoven patterns, often with plaid or striped designs. A handwoven Gho for a wedding or special occasion can be very expensive, costing in the thousands of dollars.

For formal occasions, men wear a silk shawl called a Kabney, draped over the left shoulder and the right hip. It is compulsory for men to wear a Kabney when visiting monasteries, government offices and for formal occasions. The color of the Kabney indicates different professions or levels of government.

In 1989, the fourth King enacted a law to require all Bhutanese men and women to wear the national dress for professional and government jobs, and formal events.

A Tradition of Intricate Handwoven Fabrics

Bhutanese textiles are recognized worldwide for their amazing color combinations, sophisticated patterns, and intricate weaving techniques. The weavers, mostly women, are not only brilliant creators of beauty but also the inventresses of artistic skills that have been developed and taught for centuries. Bhutanese people take great pride in their national dress. The tradition has evolved through many generations and people work hard to respect it.

A weaver may work 10 to 12 hours per day for over a year to produce a single textile piece. The technical skills of Bhutanese weaving are taught in a six-year course at Royal Thimphu College and The Royal Textile Academy.

I stopped to watch a wandering clown at the Thimphu Tshechu. “Beautiful white madame!” He yelled, motioning to me. “May you be blessed with a passionate husband and a dozen children.” Everyone laughed. These wacky monk “Atsaras” wander through the crowd like jesters, playing naughty pranks on people between dance events. Lusty chaps. See the wooden phallus around his neck? As the camera clicked someone chuckled “Nice couple.” Eccentric yet saintly, their only job is to challenge, poke fun, to find and uproot evil in the minds of mortals.

When it started to rain we headed home, but thousands of others just pulled out their umbrellas and stayed for the rest of the day.

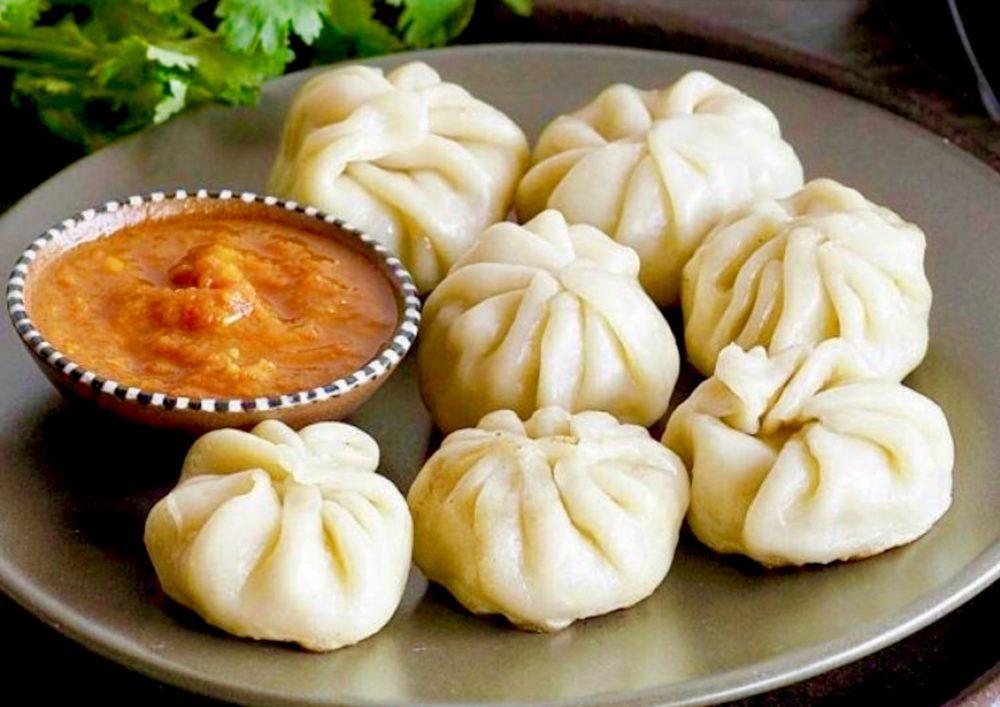

Cabbage Momos with Spicy Ezey Sauce

After a Tshechu or special occasion, momos are the #1 most loved dish. Originally from Tibet, they were called “mog mog” མོག་མོགmeaning “steamed bread”. The popularity of momos has spread from Tibet through Bhutan, Nepal, India, and all of Asia. This recipe uses cabbage however you can invent your own favorite flavor. Other delicious fillings are chicken, meat, chili peppers, cheese, spinach, peas, potatoes, etc. Makes 24 momos.

Ingredients:

- 24 Momo dough wrappers (See page XX for wrapper recipe)

- 2 cups cabbage, finely chopped

- 1 red onion, finely chopped

- 1 ball datshi cheese, crumbled (1/2 cup)

- 3 tablespoons melted butter

- 1/4 teaspoon red chili powder

- Salt to taste

Instructions:

- Place cabbage, onion, and cheese into a bowl. Add butter, salt to taste, and mix well.

- Place a tablespoon of the filling in the center of each wrapper.

- Fold over and pinch-pleat the wrapper edges to seal in the filling.

- Lightly coat a steamer with oil or cabbage leaves so the momos do not stick.

- Arrange momos in the steamer so they do not touch.

- Cover and steam over boiling water10-15 minutes or until done.

- Serve with Ezey Sauce.

Ezey – Spicy Sauce for Momos

Yep, this red-hot sauce is the real thing, and it tastes delicious with momos. You can also add optional ginger, onion, or dried chili peppers.

Ingredients:

- 1/2 cup tomatoes, diced

- 1/4 cup red onion, diced

- 2 tablespoons dried red chili

- 1/4 cup chopped cilantro

- Dash of black “Thingey” pepper

- Pinch of salt

Instructions:

Mix all ingredients well with a mortar and pestle or a spoon. Serve with momos.